Violently Happy: Hattie Stewart’s Saccharine-Fueled World Is In Your Face & Over The Top.

The realities that Hattie Stewart manifests have a carnival quality—gleaming, trashy fun with a slightly sinister undertone like golden midway tokens that rust and then jingle in your hand like they are laughing at you for believing the gold was real anyway. “Nothing brings me more joy,” Stewart says, “than taking a clean blank page and filling every inch of it with colors and imagined worlds.”

Art—especially drawing and painting—has always been a big part of her life. Cartoons were a mainstay of childhood, made apparent by her own personal doodles conjuring mermaids and cars and aliens, or tracing out her beloved characters from comics like Beano and Dandy or Beryl the Peril. There was her uncle too. He was a mural painter in Sheffield who brought young Hattie along to help realize his commissions. Art was always there. A touchstone. A happy place to return to over and again.

Stewart says, “I’m fascinated and intrigued by all forms of art and find great inspiration in every corner.” Examples of this inspiration vary wildly. Consider the following (and totally non-comprehensive) list: Hayao Miyazaki’s animated features; vintage pornography; and Martin Sharp’s acid-psychedelic cover for Cream’s album Disraeli Gears. The lattermost being “one of my biggest inspirations,” Stewart prayerfully intones.

These diverse interests first began to coalesce into her inimitable present-day style some ten years ago. Stewart was working at a bar back then. Boring shift. No action. She unpinned a photo from the wall and began drawing just for the hell of it.

She considered how her content injection totally altered the photo’s context. The photo could never be what it was, a single moment in time snared and tamed onto paper. It was that, sure, but it was also her interpreting that moment in time. The photo was intermixed with her designs and could not be unmixed. Even if she erased all her additions, she was a part of the totality of that story.

I wanted to show that there were other ways to visually engage an audience and tell a story–always towing the line between homage and satire.”

The philosophy apparent in her alterations to the photograph lingered with her throughout the shift. At home later on that evening, she continued this process by drawing all over her magazine collection.

“It was a frenzy,” she says, “It all spiraled from there. It was a very natural process and I realized—as it became a notable part of my practice—that the photography–illustration influence had been a part of my life since long before I got home from that shift at the bar. I was coming from a generation of rather traditional illustration and anything outside of that field was generally dominated with photography. I wanted to show that there were other ways to visually engage an audience and tell a story—always towing the line between homage and satire.”

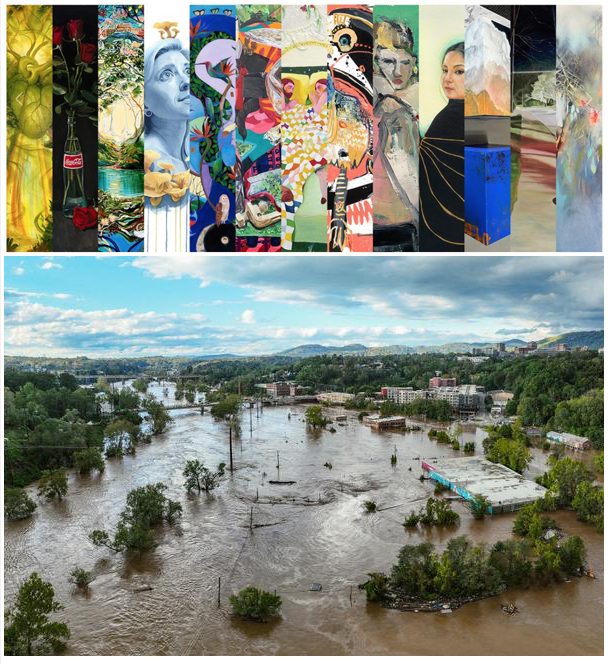

Her work on magazine covers has continued ever since that first night and grew into what is known today as ‘doodlebombing.’ Stewart’s doodlebombs enliven the covers for top-tier magazines like Vogue, W, or Dazed with bold colors and overlapping patterns and her rotating cast of zany characters.

Checkerboards and stripes proliferate, as do wide-grinning hearts and bubbly-eyed devils clad in high heels (because, as she explains, trainers are a little played out and so boring) as well as smiley faces. Just like her vast pool of influences, her style has evolved into something that seems to fuse myriad streams of thought. At once, it is psychedelic and cartoony (think Fleischer Studios’ rubber hose style) and totally surreal.

Stewart finds it useful to have this catalogue of motifs in her back pocket for elevating each project.

She says, “My most consistent patterns and characters share a commonality in being easily understood. They all emote without relying on my interpretation. So whenever I add another layer it can take a project to this different dimension. (I assume, anyway.) I have never really thought about it to be honest. I mostly just do what I like or find visually appealing, which can change depending on mood.”

These building blocks are suffused throughout her infamous sketchbook, where she workshops and develops new ideas or adds new dimensions to her rogue’s gallery of recurring motifs. Therein, the subtlest experimentations can innovate old characters and even lead to developing altogether new images to populate her imagined worlds.

Recently, for instance, searching to simplify her characters for projects requiring a tighter, streamlined design produced a revised version of her heart and also resulted in something wholly new: a butterfly. The revisions to the former—using only black lines for the eyes and paring down the mouth—allowed Stewart to bring fuller expressions to characters in tighter quarters.

She says, “Something so simple doesn’t mean much to most, I’m sure, but to me it’s such a thrill. It’s always the subtle changes that can eventually have the biggest impact on the work. I guess it’s the fine tuning that makes it all so sweet.”

A clean line is such a joy to me. If I’m stuck or having a bad day or I’m frustrated with a commission (or the world in general!), getting ideas down on paper always makes me feel better.”

Despite all the tinkering and fine-tuning that happens there, her primary sketchbook work is surprisingly polished. The casual observer will find nary an errant line nor an out-of-place block of color. The last few pages have some rough sketching, sure, but the plurality of this thinking-out space feel like completed, independent compositions.

Using this space is creatively freeing. The sketchbook acts as a meditative arena separate from her other endeavors, especially her commercial commissions, where Stewart. Looking back at previous sketchbooks, now all filled up, is like a time capsule capturing the entirety of her career, as well as a vessel for Stewart to store ideas that that might need more tinkering than she has patience for in the moment. The sketchbooks are a primordial space totally effervescing with potential—bringing newness and freshness.

“My mind never knows if an idea works unless I draw it up,” Stewart says. “A clean line is such a joy to me. If I’m stuck or having a bad day or I’m frustrated with a commission (or the world in general!), getting ideas down on paper always makes me feel better.”

That freshness has garnered Stewart much praise and commercial success. Her deft brand of cartoonish graffiti, innocent and sly and bold and graceful, has led to commissions from an envy-inducing assortment of brands and creative collaborators. Her styles, for instance, grace the packaging for Wacom products, define sartorial wares from House of Holland, have illustrated the playbill for a Noel Coward revival starring Andrew Scott at The Old Vic, and can be found printed within the pages of the same mags that she once doodl-bombed.

In addition to making art her day-in-day-out profession, commercial projects have afforded Stewart the chance to learn from other creators and showcase her work. “There aren’t really that many galleries in London that facilitate my type of art,” she says.

Creativity can’t be boxed or placed in rigid confines. I do whatever I want, as and when the inspiration comes. I find it all so exciting.”

The major difference between her personal and commercial practices is process. The former is done with Posca Pens directly onto photographs. Feeling the space, feeling that line which brings her so much joy and fulfillment, is integral to bringing that vibrant quality that makes her best work feel lived-in. Commercial work by nature requires quick and sometimes sudden changes. As such, it is much easier to keep that process digital, “which can lose some of the magic,” she says, but so it goes when art meets the practicality of firm deadlines and mercurial brand managers.

Regardless of why she is creating (e.g., doodlebombing, commercial commission, collaborating with a friend, an interactive installation at an art gallery), Stewart ensures that each project has a boutique sensibility. When a potential project arrives in her inbox, she gauges whether a spark of an idea comes to mind.

If ideas flow then it generally leads to good results. If that feeling, that inspiration, seems lacking then it may not be a good fit. The goal is always freedom of creative exploration without confinement or boundaries or guidelines.

Stewart advises: “[F]orce or try to control anything and your mind and work will suffer—well, it does for me. It is just all very fluid. Creativity can’t be boxed or placed in rigid confines. I do whatever I want, as and when the inspiration comes. I find it all so exciting.”

My mind never knows if an idea works unless I draw it up”

Things have slowed a bit since shelter-in-place became the norm earlier this year. Having an established illustration practice made self-isolating easy enough to accomplish. The unexpected emotional burden has, however, required some compromises and adjustments.

“Not being able to expel any pent-up energy with friends and family in those moments meant that I was forced into a type of self-therapy I didn’t ask for,” says Stewart.

Sheltering in place, however, has offered some space to pause and self-reflect. All the alone time has allowed Stewart to figure out what she really wants to work on. Absent the drudgeries and rigmarole of pre-self-isolation, she has luxuriated in exploring the ideas that she had neither the time nor space to fully prod. “It wasn’t all productive and easy, but I’ve fared okay,” she says.

A supercharged workflow has always propelled her forward. Stewart has never belabored just one idea for long. In her youth, she would finish one project as quickly as possible to move on to the next, to evolve her art with rapid-fire progress. While time has tempered that impulse, her drive to see the next iteration of her artmaking still underwrites every creative endeavor.

Moving forward, Stewart hopes to keep expanding her practice. Illustration will always be her primary focus. But her passions may take her into collaborations with animators (similar to her work for Kylie Minogue’s “Sexercize” music video), photographers, or other fellow artisans. Or, maybe, a dive into painting.

“I don’t just want to paint one of my illustrations on canvas. I’m still experimenting and I don’t want it to be boring,” she says. “Other than painting, though, I have found nothing that gives me the sense of calm that drawing does. To sit and draw is a therapeutic and meditative process and is so deeply personal. I just love it so much, it’s an impulse and passion that will never leave me.”*

This article originally appeared as the cover feature of Hi-Fructose Issue 56, which is sold out. Support what we do and get our next print issue as part of a subscription here and thanks for reading us!

Italian artist and designer Andrea Minini makes a living creating brand logos and graphics, but as a personal project the artist recently created the "Animals in Moire" series. A collection of black-and-white digital illustrations, the works take inspiration from the animal kingdom. But the shapes in these portraits of peacocks and pumas are anything but organic. Uniform curves outline the contours of he animals' faces. The creatures become abstracted and almost architectural, defined by mathematically-plotted shapes. The high-contrast, monochromatic patterns create the illusion of depth and dimension, yet the forms appear hollow and mask-like. Take a look at the fun series after the jump.

Italian artist and designer Andrea Minini makes a living creating brand logos and graphics, but as a personal project the artist recently created the "Animals in Moire" series. A collection of black-and-white digital illustrations, the works take inspiration from the animal kingdom. But the shapes in these portraits of peacocks and pumas are anything but organic. Uniform curves outline the contours of he animals' faces. The creatures become abstracted and almost architectural, defined by mathematically-plotted shapes. The high-contrast, monochromatic patterns create the illusion of depth and dimension, yet the forms appear hollow and mask-like. Take a look at the fun series after the jump. Digital artist Lek Chan has a series of soft, ethereal portraits that look like they could have been painted by hand, though they were created with the help of PhotoShop. Chan works as an illustrator and game designer, though her personal work has a textured, painterly quality that is more evocative of traditional portraiture than new media. On her blog, she is transparent about how she creates her works and details the steps of her process for curious viewers to follow.

Digital artist Lek Chan has a series of soft, ethereal portraits that look like they could have been painted by hand, though they were created with the help of PhotoShop. Chan works as an illustrator and game designer, though her personal work has a textured, painterly quality that is more evocative of traditional portraiture than new media. On her blog, she is transparent about how she creates her works and details the steps of her process for curious viewers to follow. Creepy creatures, spindly figures and quirky narratives compose the illustrations of Bill Carman. Pigs in suits and yin-and-yang armored headgear stare at one another – snouts pressed together – with eyes wrinkled with age of wisdom. An angry bronze-faced rabbit sits in the foreground holding a screwdriver, gazing at the viewer and threatening to unscrew the boars’ masks. Though Conunganger has an Animal Farm aesthetic, They have My Eyes evokes a Tim Burton sentiment.

Creepy creatures, spindly figures and quirky narratives compose the illustrations of Bill Carman. Pigs in suits and yin-and-yang armored headgear stare at one another – snouts pressed together – with eyes wrinkled with age of wisdom. An angry bronze-faced rabbit sits in the foreground holding a screwdriver, gazing at the viewer and threatening to unscrew the boars’ masks. Though Conunganger has an Animal Farm aesthetic, They have My Eyes evokes a Tim Burton sentiment.