Glamourpuss: The Beautifully Hirsute Portraits of Erik Mark Sandberg

“I think the next Star Wars will be made by some kid in his basement because the tech is there,” says Erik Sandberg. “A person can produce completely professional videos and audios just with the tech that’s out there right now, which is pretty fascinating for a lot of young people and I think a lot of aspiring creatives. They don’t need the mega-suite to produce certain visuals or imagery. They can just do it on a laptop and a flash drive and some software. I think that’s a really beneficial thing in terms of promoting the creative landscape.”

We’re sitting outside of coffeehouse in the Los Angeles-adjacent city of Pasadena, not far from where Sandberg is about to teach a class at ArtCenter College of Design, talking about technology and art. Sandberg himself has worked in a variety of disciplines. He paints, makes sculptures and creates short videos. In a little bit, he’ll be teaching an extension class at the art school on fine art printmaking, a course that covers historical and modern methods. His work is an intersection of the old and new, of hand and tech-driven processes, and that has in some ways informed his current work.

Recently, Sandberg has gravitated towards painting after taking a break from that to focus more on film and sculpture. He describes painting as a “slow, sluggish” process, but that’s something that drew him back to the canvas. “I’m sort of fascinated with the history and this connection to painters of the past and the museum,” he says. “I want to see if I can design a language in 2017 or broaden language… and comment on something that’s culturally relevant for the time period and the people around me.”

“There’s this component of immortality to that… that painting is going to outlive me, or that sculpture I’m making with industrial automotive paints and plastics are essentially going to outlive me.“

What is relevant to him now is the speed with which technology has advanced and how that impacts our interactions with the world. Sandberg references “better living through chemistry,” a variation of an old DuPont advertising slogan that has been riffed on over the years (perhaps most famously as the title of a Fatboy Slim album in the ’90s), as a motto for the age when he was raised. “Now, it’s better living through technology and information sharing,” he says. But, that poses new questions that are on his mind, essentially, how are we dealing with these advancements?

In a way, merging tech and art is how Sandberg started. More than twenty years ago, he moved out to Los Angeles from Minneapolis with three-dimensional animation ambitions. “I wanted to come out to Hollywood to work on Jurassic Park and films like that,” he says. Sandberg eventually was accepted to ArtCenter and, through his courses, he shifted gears. For a while, he worked as an illustrator. Ultimately, though, he gravitated towards fine art. “There was something more that I wanted to comment on,” he says, and to do that, he had to work without art direction.

By the time Sandberg finished undergrad in the early ’00s, tech was on the cusp of change. This was pre-Instagram, maybe even slightly pre-web portfolios. “You were designing a portfolio at the time when it fit into a FedEx box,” he says, but everything was about to change and he would go with that flow.

“I grew up in a very analog state and then transitioned into a digital state, so I see the value both,” Sandberg explains. “I still have an echo of: I’m going to hand-do that. I’m going to break out the pencils or the silkscreen on this part. Maybe I’ll digitally comp this part. I feel fortunate that I didn’t know the tech for so long in constructing imagery, but also I had the tech. I can add to the toolbox. I think having both skill sets is something that I enjoy for sure.”

Sandberg uses technology as a “tool” in the process and that extends to the materials he uses. He might use industrial-strength materials on sculptures and paintings. “There’s this component of immortality to that,” he says. “That painting is going to outlive me, or that sculpture I’m making with industrial automotive paints and plastics are essentially going to outlive me. I can control the state of the disposal a little bit in terms of the material that I use.”

He’ll go back and forth between methods, maybe draw on a Cintiq or silkscreen onto a painting. His background in printmaking, which he picked up while in school, and its step-by-step process comes in handy. “A lot of times, when you’re constructing works, that problem-solving road map helps and printmaking helps,” he says. “A lot of it gets embedded in your work too. Should I paint this or should I do it digitally and then screen this component on?”

“Where does authenticity live in cultural society today? These systems that we have in place now for communication and information sharing, they have to be taken a bit with a grain of salt.”

There’s a lot in Sandberg’s tool box. He has worked with acrylic and oil, etching and photoengraving. Frequently, he plays with characters that blur the line between human and monster. Their bodies are shaped like ours. Their clothes are like ours, but their covered in hair. Sometimes, they take on the appearance of werewolves with animal-like fur. Other times, the hair spirals off their faces and bodies like think pieces of clumps of brightly colored yarn or long, rolled strands of Play-Doh.

“I don’t usually take photo reference or things like that,” he says. “Usually, a lot of that comes out of expression in my mind. Once in a while, I’ll use some photo reference with a very specific lighting source.”

In “Girl with Sunset,” pink hair covers almost the entirety of the head—only the character’s eyes and mouth are fur-free—and sweeps back into the sides as if it has been windblown. In “Rapala” (2016), a man and woman cruise in a BMW. Black hair knots up on their faces. The characters are just human-like enough to become relatable creatures.

Previously, Sandberg was concentrating on photography and film. At the time, he was living in a large warehouse in Atwater Village, a neighborhood near the L.A. River. It was a largely industrial area, so he could work late and make noise on these complicated projects. He would build “big, elaborate” costumes for the shoots and bring in friends to model. He would offer some direction to the models, but Sandberg, who says was intrigued by the screen tests of Andy Warhol’s players, also wanted to see what the models could bring to the image. “It was a really interesting experience,” he says.

In “Beach Day,” waves roll over the sand as a model, Leah Raquel, sits on a swing and slurps a thick black concoction through a long, thick straw. The model flirtatiously plays with long tendrils of yellow hair that, close-up, look like rolled up pieces of plastic. Appearing more like a Creature from the Black Lagoon-made-waste, the model gulps

down the drink with the excess falling against hair. Seductive poses meet the ugly effects that humans have on the environment. “The Washing” is a little less obvious commentary, maintains that creepy, goopy monster vibe.

“With photography, there is a sort of truth to them. There is a sort of reality to it. It’s able to manipulated so greatly through the pixels, but there is this inherent truth to it,” says Sandberg. “You see components of it through advertising. Here’s this because it’s believable. When you see that manufactured family on the catalog for the mall, you believe it even though we know it’s all actors. It feels like, the scenario feels somewhat believable.”

That believability inherent to photography and film brings up more questions for the artist, especially in an age where technology has made it much easier to manipulate images. “Where does authenticity live in cultural society today?” he asks. “These systems that we have in place now for communication and information sharing, they have to be taken a bit with a grain of salt. Obviously, if you’re in the visual arts community, you’re a bit more savvy… To maybe the average individual without that visual sophistication, how do they know what’s fully believable or real? Does it matter?”

At the time of this interview, Sandberg was part of a group exhibition at 101/Exhibit in West Hollywood called Figurative Futures. Amongst the work he contributed to the show was “Arboretum,” a 2016 ink and acrylic piece that depicts a thin woman with black hair curling and clumping as if it were air-drying after a day in the pool. The hair crawls down her neck and shoulders, under the straps of a cut-off Black Flag tank top. The wire of her earbuds falls towards the gizmo in her hand. Behind her is a wallpaper-like scene of plant leaves.

Amongst Sandberg’s current influences are flowers and plants and that connects to his digital interests. He recalls a condolence email that he received after his mother died a few years ago and how the note featured a .gif of a wreath. “I like the fact that it doesn’t keep that normal, cyclical aspect of receiving something,” he says. “The fact that it’s still twinkling in the inbox, in the email, I find slightly fascinating in form and culture.”*

This article originally appeared in Hi-Fructose Issue 45, which is sold out. Support what we do and get our latest issue by subscribing to Hi-Fructose here.

Casey Weldon crafts surreal, sometimes absurd paintings that play with the everyday and the otherworldly alike. The artist, based in Washington, D.C., is featured in a new show at Thinkspace Gallery in Los Angeles. “Sentimental Deprivation” continues the thread of that duality in the artist’s work. The show starts June 3 and runs through June 24.

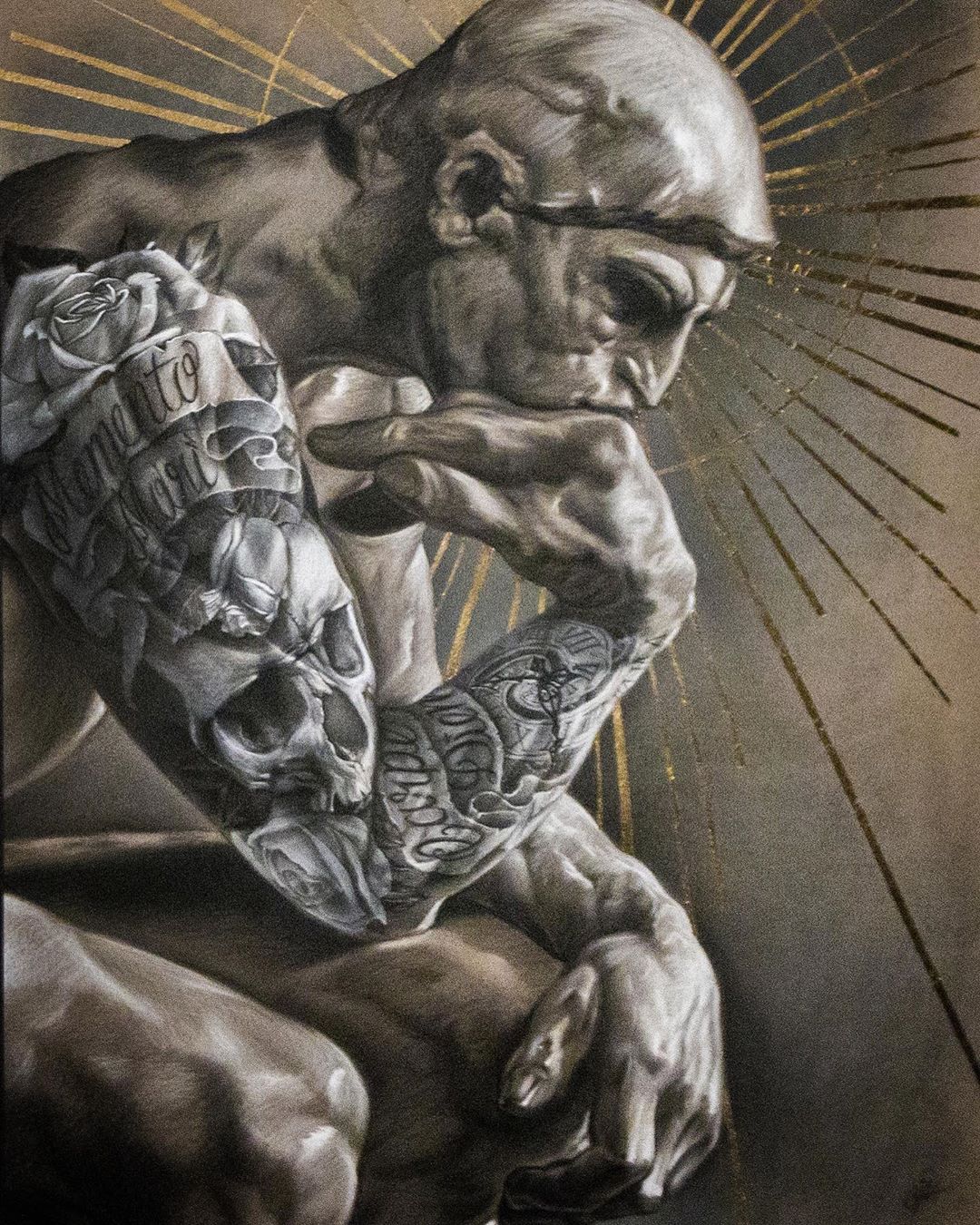

Casey Weldon crafts surreal, sometimes absurd paintings that play with the everyday and the otherworldly alike. The artist, based in Washington, D.C., is featured in a new show at Thinkspace Gallery in Los Angeles. “Sentimental Deprivation” continues the thread of that duality in the artist’s work. The show starts June 3 and runs through June 24. Carlos Mendes, who works under the name CIAS, is a painter and tattoo artist with a penchant toward ancient art history. He shared some of his recent work that blends these worlds in the show "Indelible" at Espaco Exibicionista Gallery. Mendes is based in Lisbon, Portugal.

Carlos Mendes, who works under the name CIAS, is a painter and tattoo artist with a penchant toward ancient art history. He shared some of his recent work that blends these worlds in the show "Indelible" at Espaco Exibicionista Gallery. Mendes is based in Lisbon, Portugal. Tunisian artist Atef Maatallah paints people on grainy, monotone backgrounds to highlight the inner worlds of his characters. Maatallah often paints diptychs, in which one panel features only a single object such as a tea pot or small animal. Purposely separated from the human figures, the objects serve as outer manifestations of the peoples' fears or desires. For example, an elderly woman with sun-baked sunken cheeks watches with a solemn expression as the feathers of a skinned bird — its' complexion the same color as the woman's — float downwards. In another image, a forlorn mother looks down as her two children sleep; one in her arms, the other slouched against her back. In the background, a bare light bulb hangs. The light is out.

Tunisian artist Atef Maatallah paints people on grainy, monotone backgrounds to highlight the inner worlds of his characters. Maatallah often paints diptychs, in which one panel features only a single object such as a tea pot or small animal. Purposely separated from the human figures, the objects serve as outer manifestations of the peoples' fears or desires. For example, an elderly woman with sun-baked sunken cheeks watches with a solemn expression as the feathers of a skinned bird — its' complexion the same color as the woman's — float downwards. In another image, a forlorn mother looks down as her two children sleep; one in her arms, the other slouched against her back. In the background, a bare light bulb hangs. The light is out. Colin Chillag's paintings blend the vivid and realistic alongside unfinished, preliminary parts of the work intact. The effect is not only disconstructive in looking at how memory functions in art, but also exploring the process of painting itself. Chillag was featured in Hi-Fructose Vol. 19. He was last featured on cctvta.com here.

Colin Chillag's paintings blend the vivid and realistic alongside unfinished, preliminary parts of the work intact. The effect is not only disconstructive in looking at how memory functions in art, but also exploring the process of painting itself. Chillag was featured in Hi-Fructose Vol. 19. He was last featured on cctvta.com here.